In 2003 the Minoan Palace of Knossos was submitted for inclusion to the list of UNESCO World Heritage sites. Today, the fate of some of the world’s most treasured landmarks is still mired in a bureaucratic bog. In this follow-up report, I engaged key decisionmakers in an effort to glean a better understanding of the situation. Here is what I discovered.

“I am optimistic and hope that Knossos will be included soon.” – Dr. Kostis S. Christakis, Knossos Curator

In my last report, I delved into the historic and cultural significance of Knossos Palace on the island of Crete. Europe’s oldest city, the site outside Crete’s capital has been inhabited since Neolithic times 9,000 years ago. It was the famous archaeologist, Sir Arthur Evans’ who shined the bright light of discovery on Knossos and elsewhere, and who helped build what is currently known of the vast historical/cultural significance of the Minoan Civilization which has piqued the interest of the world. Knossos stands today as the centerpiece of immeasurable human heritage. A heritage some hope and pray will be preserved forever.

Searching the Diplomatic Labyrinth

The fact that this treasure of human heritage has not long-since been included in the UNESCO registry of sites astonishes Cretans, Greeks, and every regular citizen of the world I’ve discussed the case with over the last few weeks. However, at the official level, the responses I’ve gotten have been mixed, often confusing, and dispassionate to an extent I find disturbing. In my effort to get answers any citizen is entitled to, I’ve run into a labyrinth Theseus himself could get lost in. Furthermore, if my suspicions are correct, the Minotaur at the center of this Knossos maze will not be defeated so easily.

Since my initial interest in the Knossos UNESCO bid came about via a press announcement of Heraklion Parliamentarian Dr. Nikos Igoumenidi, I contacted the SYRIZA (ΣΥΡΙΖΑ) political leader to ask about his impressions and the current status. On the longstanding situation, Dr. Igoumenidi first registered a deep concern and answered other important questions. The Crete official offered this first:

“We are astonished of the fact that a monument of world cultural heritage such as Knossos that is out of the UNESCO’s list.”

The Cretan politician went on to explain a new so-called “serial registration” that includes not only Knossos, but the Minoan centers at Kydonia, Phaistos, Malia, Zakros, and Zominthos. I first learned of this serial bid from a communique with Ms. Constantina Benissi, the archaeologist who is Head of the Department for the Supervision of Greek & Foreign Scientific Institutions & Coordination of International Cooperation & Organizations Directorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities for the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

I do not wish to make Ms. Benissi’s exceedingly long job description an issue here, but the email signature is ironically indicative of the greater problem. Like the other officials in my truth quest over Knossos, the notable archaeologist was professional to the letter, and politically correct too. However, what made me skeptical about this collective UNESCO bid was that fact it took a recent near-revolt in Athens to have Knossos and other Greek monuments taken off the list of “sellable assets” available to pay off Greece’s staggering debt earlier this year. The fact that Greece’ most valuable cultural assets had been put on the chopping block for any reason, it cast a shadow on an already ridiculous situation. Nevertheless, Ms. Benissi’s detailed outline of the 4-Stage process necessary for Knossos or any site to be listed a UNESCO World Heritage site. I was stunned to learn that in the case of the most famous Minoan palace, western civilization’s oldest city is only at Stage -1 after 16 years of alleged effort.

What this means, if I understand Ms. Benissi’s emails correctly, is that the Palace at Knossos is still only nominated for UNESCO recognition. According to her detailed explanations, neither the World Heritage Centre, or the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), nor the World Heritage Committee has evaluated the Minoan Palace at Knossos for UNESCO inclusion. For the sake of accuracy, here is what Ms. Benissi sent me on Stage-3 of the process:

“Once the nomination file is checked by the World Heritage Centre for completeness, it is independently evaluated by the appropriate advisory body as mandated by the convention. Respectively, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), provide the World Heritage Committee with evaluations of nominated cultural and natural sites, respectively.”

Consulting the Heritage Oracle

Ms. Benissi enumerated further the complex process by which UNESCO sites are adopted to the famous list. The process, which is focused on things like heritage value, levels of protection for the site, the management regime, and so forth, is further complicated by an unimaginable list of stakeholders involved in the process. Add to this the administrative boondoggle of “rebooting” the big of Europe’s oldest city, and you’ve got a real mess. So, learning from Ms. Benissi and other stakeholders that Knossos is now back at Stage -1 because of the serial nomination process since 2014 is nothing short of astonishing.

According to Ms. Benissi and Dr. Igoumenid, the Ministry of Culture and Sports is moving forward with the Region of Crete in the preparation of the Minoan Palatial Centre nomination file. In addition, I have been notified that “a series of works concerning the conservation and enhancement of all the proposed palatial centers has been undertaken.” However, my follow-up questions about resources, staffing, and so forth, have not yet be addressed. What I have learned is that with regard to our heritage, the European Union and the academic underbelly of regulation is a vast swampy bog of diverse stakeholders, institutions, and regulatory monsters Herakles and a Pantheon of heroes could not move. I have limited time and space, so I’ll offer one example of the European Association of Archaeologists.

Reading meeting minutes and papers from the EAA and other key organizations involved I found a conflict of ideas and strategies within an already complex and encumbered system. Schools of thought on how our heritage should best be preserved is but one area of conflict these discoverers and guardians of our legacy task themselves with. At a conference in Athens in 2017 discussing many of the questions I’ve asked answers to, Ms. Benissi and colleagues were in focus for a paper entitled “Management Plans: A tool for participative decision-making,” which deals with operational inclusion and exclusion of certain decision makers. Within this paper, I found out the essence of the beast that promulgates the heritage-interruptus (my term) affecting Crete’s greatest historic treasures. The authors of this report practice all the forms of flattery and backslapping the United States Congress is famous for. It makes no difference whether or not the various officials have good and honest intentions, or not. The system is nonetheless and unplausible one where public inclusion in the process is concerned.

Within the “study” above you’ll recognize the World Heritage Center as the temple for archaeological priests and priestesses to pray at. For the lack of a better explanation here, suffice it to say the authors of this paper consider the Ministry of Culture of Greece at the top of a Pantheon of vested interests that resembles a Meritocracy with demagogical intent. At the aforementioned conference, Sophie Hueglin, Vice-President, European Association of Archaeologists addressed the conservative status-quo philosophy of archaeological heritage management, versus a new liberal approach that considers everyone a stakeholder. In my opinion, these efforts will simply amount to officials stacking more bureaucracy on top of an already cumbersome system.

Thundering Thunderbolts of Zeus!

With no answers to the question of whether or not individual Minoan sites can “make it” as UNESCO treasures, I again tried UNESCO’s Media Chief, George Papagiannis in Paris. I’ve still received no answer there. A followup email to Ms. Benissis at the Greek ministry also met with no enlightening response. Heraklion Parliamentarian Dr. Igoumenidi did offer this with regard to proceeding more “decisively” with these inclusion bids:

“The so-called “serial registration,” which allows for the gradual inclusion of monuments that are included in the Minoan Culture Center section, seems to give me the necessary momentum to do so.”

To Dr. Igoumenidi’s credit, his final comments to me on social sensitization being fundamental to greater mobilization actually give this writer hope. However, the list of names, stakeholders, organizations, agencies, and the lack of a real communication strategy cause me to doubt. Even though I’m informed Minister of Culture, Myrsini Zorba is personally tracking the implementation, I’ve been unable to secure verifiable proof that anyone is doing anything other than talking. What’s most disturbing is the absolute lack of passion by any official I’ve talked with. Heraklion’s representative is the only actor who registers dismay over the lackadaisical Knossos effort.

Our Cultural DNA Kidnapped

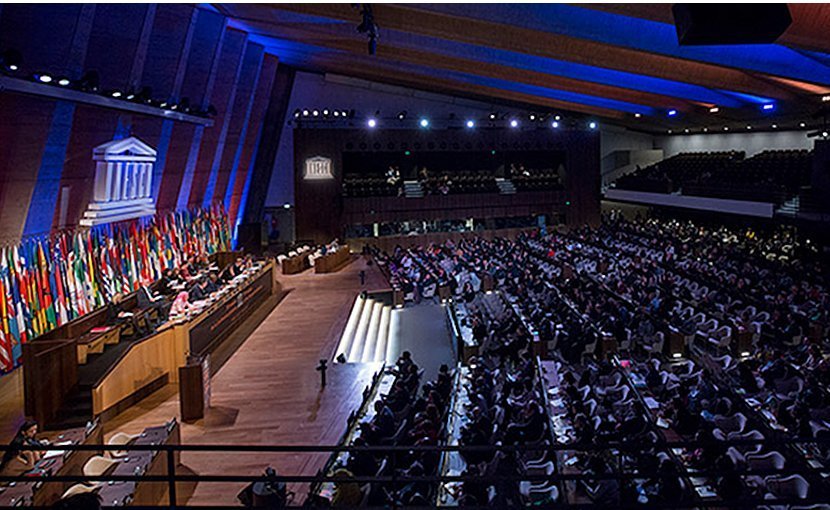

I want to finish this report by focusing on what I see as the two biggest problems of the UNESCO system of heritage preservation. First and foremost, the system has taken on a life of its own – a life that has metastasized into an almost uncontrollable mutation of what the United Nations effort once stood for. Secondly, the system is now a mostly dispassionate club based on an elitist hierarchical structure or bureaucracy that is self-perpetuating.

If you take the time to investigate the “world” of ministries, NGOs, academics, politicians, business concerns, and conference agendas that occupy the time of those tasked with preserving our monuments you’ll quickly be stymied and amazed. The UNESCO “game,” if I may call it that, is a sub-culture of its own. Take for example the European Heritage Heads Forum, which is one of a hundred events/gatherings professionals in the arena attend and contribute to. The video above shows attendees to this forum joining in the gleeful rendition for the Ode2Joy challenge. Clearly, the Luxembourg event lifted Mosel wine region revenues, if my musical ear is correct. Now, please multiply this heritage brainstorming event by 50 or so. There over 150 listed by Europa Nostra (Our Europe) alone, so there’s no shortage of conferences and dinner parties. Let me quote here from the 2018 “Berlin Call to Action” meetup under the auspices of the 2018 European Year of Cultural Heritage and the European Cultural Heritage Summit:

“Cultural heritage is unique and irreplaceable. Yet it is often vulnerable and even endangered. Therefore, it is our collective task to preserve this treasure so as to transmit it for further enjoyment and (re)use to future generations.”

Finally, the UNESCO process and the “congregation” of decisionmakers who make up our cultural clergy live in a different world. I cannot imagine the average shopkeeper here in Heraklion having anything whatsoever in common with these people. Even the wealthiest resort owner on Crete is so far detached from the process, no one would believe it. We live in a world where politicians and their subordinate ministers speak of the normal people like we are problem children, at best, and imbeciles who should be bypassed in any decision process, at worst. To put it bluntly, the individual citizen is worrisome – a bother – disruptive in the process of bigger thinking. I do hope I am not too harsh here. But this is my impression. To understand how I got to this sorry state, please read this report that details how the EU’s brightest lunatics suggest citizens “interpret” their heritage.

“While populism, protectionism and nationalism have been challenging such statements for some years, the decision to hold a European Year of Cultural Heritage offers an outstanding opportunity to introduce heritage in a way that makes citizens reflect upon the privileges and requirements that come with Europe’s shared values. This opportunity must not be missed.”

If you read this correctly, the people engaged in preserving this Minoan heritage and seeing to it that we all have a role, they’re on a liberal political agenda and determined to forge a “shared values” public relations dogma. The “shared” heritage involves local, regional, national, and collective heritage, in case these geniuses at the Interpret Europe NGO had not noticed.

The city and civilization that was the foundation of Europe still lie buried beneath the fine sand of Crete, and underneath a monstrous mountain of ineffectiveness, elitism, and ridiculous bureaucracy. This month the Council of Europe certified a European Route of Industrial Heritage, the Iron Curtain Trail and other “paths” our heritage took, but somehow our starting point remains obscured. UNESCO’s World Heritage Website has been nominated for a Webby Award this month, but their head of communications cannot take the time to inform the public about the Minoan serial registration! World Heritage Journeys, they only pass by a civilization welded into or human DNA. Mighty Notre Dame will be rebuilt with billions in public donations, while Phaistos Palace and the others sit in solemn dignity overlooking a long lost heritage very few will revisit.

[…] by hand, uncut and undamaged, in order to preserve the mysterious energy the sacred mountain of Knossos is said to possess. For those unfamiliar with such stoneworking craft, creating seats of an […]