At the far eastern corner of Crete Island, an amazing prehistoric city once existed. Visiting the ruins left at Itanos once gets the sense of lost time, and of the powerful and prosperous people who once lived there. Ancient Itanos was one of the strongest cities in Crete, but little is known of the ancient port of commerce from Neolithic to early Minoan times. And underneath a beautiful alluvial plain, there lies something more.

Greatness on a Cretan Breeze

When we visited the archaeological site of Itanos for the first time a few days ago, everyone in our party was taken at first by the beauty of the place. Walking the nearby beaches and to the top of the promontory overlooking the vast ancient port, we all commented on the “good vibe” in residence there. If you visit, you will be overcome by the same feeling, I am sure. Something amazing happened at Itanos at the dawn of human history. This is the permeating feeling I get from the place.

Overshadowed by more famous palatial centers at Knossos, Malia, Phaistos, Kydonia, and Zakros, Itanos is an afterthought of history. But one look out over the rich alluvial plain behind the site reveals what I believe will soon be an amazing revelation. The scope of Itanos’ importance and power far excede what a casual survey suggests. One legend has it that the city was founded by one of the Cretan Kouretes. These were armored dancers who protected the infant Zeus from his cannibalistic father Cronos.

At the Whim of Gods

Homer also recounted 90 fabulous Cretan cities, and it’s my belief pre-classical Itanos was a major one – perhaps one of the most powerful. Other cities of Crete founded by these Kouretes include Biennus in the far south of the island, and Eleuthernai, in the Amari Valley.

Each of us is all the sums he has not counted: subtract us into the nakedness and night again, and you shall see begin in Crete four thousand years ago the love that ended yesterday in Texas. – Thomas Wolfe

Minoan Itanos encompassed everything from Cape Samonio (current Cape Sidero) to Cape Erythrae (current Cape Goudouras). The glass and Tyrian purple trade that made the city rich in later times played a secondary role to the metals and ceramics trade that surely took place even before the prepalatial period.

To support my theory, beyond the normative sense of intense magnetism of the place, recent seismic refraction and reflection techniques employed at the site detected the ancient port of Itanos and mapping the bedrock of the area, covered by alluvium deposits.

Itanos, unlike most other large Minoan sites, has witnessed very little traditional archaeological excavation and preservation. So, the findings of researchers using advanced ground-penetrating radar surveying and electrical tomography at the site takes on added significance. Back in 1993/1994, the Institute of Mediterranean Studies – F.O.R.T.H., the French School of Archaeology in Athens and the Technical University of Crete used these and other techniques to get a 3-dimensional model of what still lays hidden at Itanos.

The results, simplified, showed subsurface alluvium layers of the site contain at least 2 occupation levels at varying depth from the current surface of the ground. Another seismic grid mapping was carried out by the Laboratory of Applied Geophysics in September 2002, and another in 2003 by Vafidis Antonios, Poulioudis George, Kritikakis Georgios, Sarris Apostolos. The latter survey showed that the ancient port of Itanos may have extended at least another 100 meters inland from the current shoreline. The sea level in the region during the second millennium BCE was apparently 1e2 m lower than at present (Sneh and Klein, 1984; Flemming and Webb, 1986; Kayan, 1988, 1991).

The survey did not take into account sea-level 5,000 years ago, which if I am correct, would have been as much as much as 5 meters lower than today on Crete. If this is the case, the sediments scientists are testing are probably like those off Priniatikos Pyrgos, near the Istron River on Mirabello Bay. In that case, scientists believe the tsunami which swept over northern Crete created a backwash of sediment once the waves receded after crashing into the higher elevations near Ha Gorge. Without going into an ancient geography and geology lesson, the area of Itanos was undoubtedly reshaped during the Late Minoan IA (LMIA) period. This would also explain the limited knowledge we have of what Itanos looked like in Neolithic or early Bronze Age periods.

Swept from History’s Pages

According to the report Cretan Cities: Formation and Transformation, the north-east corner of Crete was not deserted during the centuries preceding the founding of Itanos. In fact, a city-state probably existed that included what is now Itanos and Palaikastro. In addition, scientists believe there may be an undiscovered Minoan palatial center somewhere in the area. Surveys of the whole area reveal Neolithic and Early Minoan settlements dotting the landscape of the hills overlooking Itanos. The book Final Neolithic Crete and the Southeast Aegean identifies seven sites north of Paleakastro, and it seems likely there are dozens more.

The fact that Itanos seems to be abandoned at around the end of LM IIIB, and Palaikastro at about the same time, probably had more to do with some religious/political upheaval. But the destruction that must have taken place in the area ofter Thera exploded surely rearranged the landscape years before. Scientists now believe a tsunami of between 15 and 35 meters in height crashed into Crete at a speed of around 290 miles-per-hour only 13 minutes after they were created off what is now Santorini. A visit to the area reveals a rugged landscape where it’s easy to visualize whole chunks of coastline ripped off of Crete by this devastating force. Itanos, in particular, seems as if the backwash of this tsunami reshaped the harbor and the depression inland. The dramatization below from the BBC’s Atlantis provides a window into what that day must have been like.

Today, thousands of years of erosion, later civilizations, and other geological-climactic effects have left us with just a piece of the puzzle that was Itanos’ role in Minoan times. I can only speculate about the real effects, but I intend to do more study on Itanos. The work of Hendrik J. Bruins, J. Alexander MacGillivray, and other researchers back in the mid-2000s support a theory I have about what lies underneath the current Itanos site.

More recent mapping of part of the Itanos region has revealed a lot more about early habitation, but there are still many holes in the puzzle or late Neolithic-EM activity. Most of the sites that were mapped are in the highlands, with the valley’s and lowlands seemingly erased until the neopalatial period. I believe the reason for this is the same tsunami effect discussed previously. Perhaps mine is an oversimplified geology/geography opinion, but the event researchers describe might certainly have washed the late stone age off the Cretan map. Scientists from the Belgian School at Athens worked the site from 2011 until 2015 and assumed that Itanos was more or less uninhabited until the MM period. I may be wrong, but I think this overlooks what a world-changing event like the Thera eruption would have done to these people and the landscape.

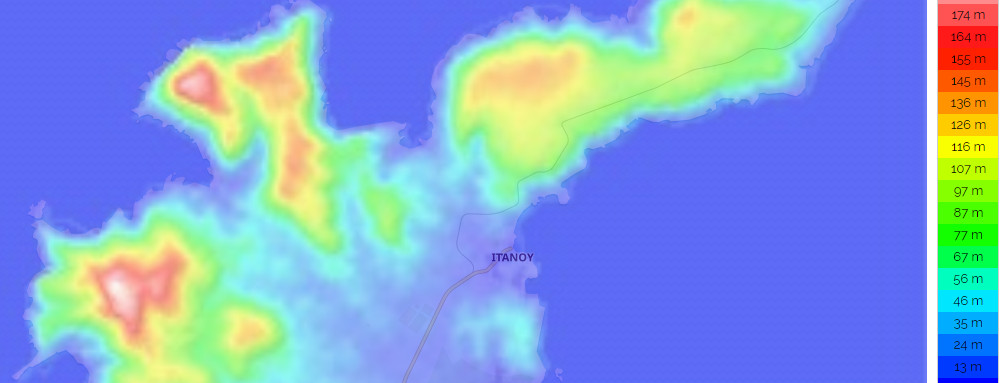

A paper by John Antonopoulos of the Civil Engineering Department, School of Engineering, University of Patras briefly discussed tsunami inundation at Itanos, Palaiokastro, and Kato Zakros back in 1992. This study also points to the work of Professor Pfannenstiel (1960), which found layers of sea-borne pumice in sediments of a postal-glacial terrace 7 meters above sea level, north of Jaffa (Tel Aviv). According to Pfannenstiel, this would have meant the tsunami at its origin off Thera would have been over 50 meters high. The crude elevation map below gives you an idea of how a tsunami coming ashore at the would wash through the center of the Itanos region, taking with it huge chunks of human habitation there.

Magnificence Undiscovered

In conclusion, I did some amateur topography and hydrology work using primitive mapping tools. What I discovered seems significant. If a pair of tsunami waves of 25-35 meters in height struck the northeastern shore of Crete, the Cretan Sea would have literally washed the lower areas of Itanos clean. The lowest point of the ridge running west-southwest to east-northeast is 35 meters above the current sea level. It does not take much imagination to visualize the catastrophic effect. And what if the dual tsunamis were bigger? If I am right, the reason archaeologist do not find late Neolithic evidence, it’s because it was washed out to sea or covered in meters of backwash sediment. And as for the supposed “lost palace?” Well, I am being highly speculative now.

The “Itanos” that is missing. The Early Minoan period commercial center which dealt with Rhodes, Egypt, and the Assyrians, it does not exist in the current archaeological realm. The Itanos region feels like a place where a monumental discovery will be made in the future. I do not have solid proof yet, but the science and the normative aspects of this place may finally explain what actually happened to the Minoans. I am only certain that renewed scientific interest in this region will benefit archaeologists and society overall.

Update 11/1/2019: Dr. Jan Driessen, one of the most respected archaeologists in the field, cautions against adopting wholesale a tsunami event ending the heyday of the Minoans. He cautions us to not jump to conclusions because of the overall lack of geoarchaeological evidence for tsunamis. And granted, there needs to be a lot more work done. In this recent paper, entitled “The Santorini Eruption. An Archaeological Investigation of its distal Impacts on Minoan Crete, Quaternary International, “ Dr. Driessen creates a bigger window into what Crete was like in the Late Minoan period following the Thera eruption. In the end, a lot more work has to come from Earth scientists before a crystal clear picture of Minoan Crete before and after Thera exploded can be painted.

As I read through Dr. Driessen’s and other Minoan era expert’s research, I cannot help but reflect on the effects of a more recent volcanic catastrophe. The Krakatoa eruption and ensuing tsunami of 1883 was an Earth changing catastrophe. It may be a simplistic comparison, but the fact that Krakatoa was of a magnitude of VEI 6, and that new data shows Thera was a VEI 7 event, it spurs my curiosity.

To be continued…