Was the Keftiu civilization the basis for the Atlantis myth? The question of the existence of such a myth makes most Aegean archaeological experts cringe. The fact of the advanced Atlanteans of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias is, at best, categorized as allegory. Still, heavy circumstantial evidence supports the ancient story’s authenticity. I believe that the Keftiu (popularised as Minoans) were the Atlanteans.

You can ask a dozen Aegean archaeologists if Crete island, one known as Keftiu, was the basis for Plato’s Atlantis, and few will entertain even the idea of it. Even the most open-minded and enthusiastic among them have more questions than answers. One renowned Aegean archaeologist, Alexander “Sandy” MacGillivray (pictured below), has suggested that Crete could not have been Atlantis because he says Plato was adamant about the sunken continent being in the Atlantic Ocean, beyond the so-called Pillars of Hercules. Even so, MacGillivray’s fantastic work concerning the massive Thera tsunamis that struck the Crete and destroyed all the major Minoan cities has reignited the Crete/Atlantis connection in recent years. MacGillivray has gone so far as to discuss the theoretical high culture of Atlantis (see Getty interview), but it’s a huge leap to do more than have conversations about the nature of the famous lost civilization. At least at this point in time.

A critical challenge in investigating and substantiating the claim that the Keftiu were the people of Plato is the professional/scientific constraints all archaeologists face. The scientific method is built on empirical evidence, on what we know. While the definition of ’empirical’ can be flexible, depending on the continued discovery, accepting a folk memory of a real ancient civilization swallowed by the sea is a step too far for many. Yet, as I mentioned earlier, there is logic and circumstantial evidence. More importantly, we all share the shared ethereal experience regarding oral tradition. If there is one “fact” we can all agree on, it is that what we do and do not know is a universe compared to a pea.

Atlantis On the Liminal Edge

Dr. Beth Ann Judas’s paper for the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities (SSEA) in 2014 provides more such evidence. In “At the Edge of the World: The Keftiu as a Liminal People in Early New Kingdom Egypt,” Professor Judas’ paper suggests that the Keftiu “inhabited a liminal space at the edge of Egypt’s known world.” The learned expert takes us further into seldom discussed Keftiu spirituality and mysticism in her work “Keftiu and Grifins: An Exploration of the Liminal in the Egyptian Worldview.” I quote directly here from the book “Current Research in Egyptology 2014:

The grifin is a mythical animal that is part of both the Bronze Age Egyptian and Aegean iconographic corpora. It inhabits the space between the known and unknown, such as the world between the living and the dead and is a creature that is a symbol of liminality. Additionally, the Egyptians recognized that the Aegeans had their own grifin, which had similar associations with the sacred world.

To delve into Keftiu religious beliefs here is far too great a task for such a short thesis. However, a work by Bernard C. Dietrich entitled “Death and afterlife in Minoan Religion” bears mentioning here. On the subject of Keftiu’s core beliefs and their importance (reflection) on their civilization, the so-called “cult of the dead’ and the belief in continuity in the universe punctuate the probable worldview of these people. The late professor writes:

The belief in a continued separate existence in sorne otherwordly fourth dimension presupposes the notion of survival in some form of individual identity after death.

The Puxn, which from Homer means ‘life’ rather than the soul, is an existential element that was said to fly away or flutter off like a bird when the hero dies. This life spirit was supposedly even in animals. According to Knossos excavator Sir Arthur Evans, the soul is still pictured as a butterfly in modern Cretan folklore. Of course, we must delve more deeply into multi-dimensional existences, the Mythological King Minos as the gatekeeper to the afterlife, and especially not into the realm of otherworldly discoveries at various sites on Crete. Keftiu animism, the belief in divinity in all things, is an aspect that should be mentioned. In addition, the ancient Egyptians’ reference to Keftiu as the “land of the dead” seems significant for no reason but to prove my thesis of Keftiu isolationism.

The Keftiu: Sons of Atlantis

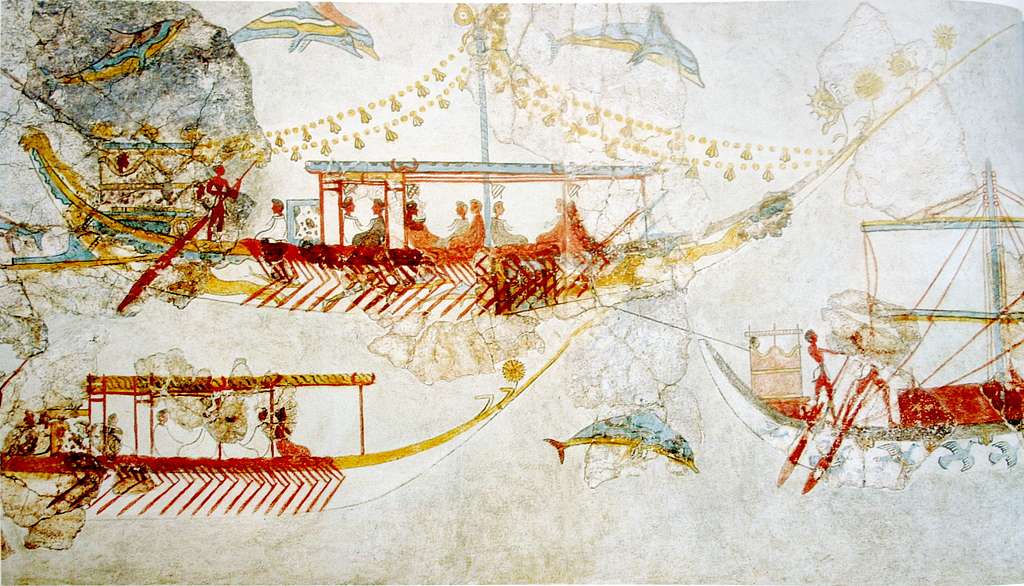

While researching for this report, an idea I’ve had for some time resurfaced. “What if the Keftiu (or Atlanteaenigmaticinegmatic for a purpose?” What if prosperity and power were veiled beneath an impenetrable bubble (shield) like so many isolated cultures? For my purposes here, one definition of the term “liminal” further illuminates ideas about the Keftiu being highly isolationist in their geostrategic practice. Liminal, in the context of “…situated at a sensory threshold: barely perceptible [def]…” could depict a society or civilization both feared and almost largely unknown even to the Egyptians and especially their supernatural ideologies. This may be a stretch into the imagination, but many experts acknowledge Keftiu as the world’s first thalassocracy, and not one disputes their maritime prowess throughout the Bronze Age.

During the time Sandy MacGillivray was excavating Palaikastro, the Crete’s far-east studying probable Thera eruption tsunami devastation (proving a theory few believed), Costas Synolakis, from the University of Southern California, was quoted saying:

The Minoans are so confident in their navy that they’re living in unprotected cities all along the coastline…

This statement weighs heavily for my theories of Keftiu’s isolationism and “relative” position in the ancient world throughout the Bronze Age. Somehow, intuitively, the Keftiu as inheritors of Atlantis’ ideas, technologies, and even superiority hits me here. What if the Atlantis catastrophe was much earlier than the Egyptian or Keftiu development? Again, this is a subject for future discussion. It’s enough to realize that the Plato account was Grecocentric and that if Atlantis did exist, earlier storytellers probably labelled and located in a completely difference frame.

A Continent Lost in Context

So, returning to the current discussion where scientists view Plato’s fantastic story, a few bear clarification/discussion here. Identifying Keftiu as Atlantis or the Keftiu (people) as descendants of the Atlantians seems unlikely if the retelling of the Atlantis story has been convoluted. Take the assumption that the Pillars of Hercules are at the Straits of Gibraltar. Dr MacGillivray expressed his reservations with the PBS and in several documentaries. No matter how open-minded and curious the world’s best experts are, they are handcuffed to provable facts. On this location issue, it’s important to note that the oldest account of Atlantis (discussed later) has been altered with the retelling. A case in point is how Plato and Aristotle, Ephorus (405 BC), Eratosthenes (276 BC) and Strabo (63 BC) all relocated the pillars to Gibraltar.

It seems more logical to assume that only the ancient Greeks, from before 400 BC, were the only possessors of the oldest recollections of the lost continent. After all, we are speaking about aeons of time; please consider how everything changes with time. If we put aside the Gibraltar case, we can reexamine many possibilities and some probabilities. Only a few archaeologists today are willing to do this. The average person has little or no idea that these “pillars” could have existed at locations only the ancients found significant or as waypoints. One such area is at the outlet of the Gulf of Laconia in Greece, where a so-called Pillar Cult was once practised. Another likely possibility is that Plato’s demarkation point to Atlantis was located in the Gulf of Gabes in Tunisia. I’ll wager that only one or two reading this will have heard of such. I’ll discuss the former in another paper, focusing on the Libyan theory here.

In what is now Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, a Mesolithic civilization once thrived as far back as 10,000 BC. Certain geographic features of the Atlantis accounts hint at the great salt lake of Chott el Djerid, which had once been connected more directly to the Libyan Sea in what is now the Southern Mediterranean. Most experts say Plato’s mention of the lost continent was taken from outside sources, most notably poetry derived from a poem of a very old Egyptian priest, Sonchis of Sais (594 BC?). The priest was a holy man who related the Atlantis story from the ancient Temple of Sais (from 3000 BC). The temple, once the capital of Lower Egypt, was dedicated to the Egyptian creation/warrior goddess Neith. The question arises, “Would the most learned man in ancient Egypt (if Sonchis existed) be more likely to have a keen knowledge of a Libyan (or even Greek) passage to Atlantis? Or, would a scholar who lived 5,000 years ago speak of a place the Egyptians could not catch a glimpse of?

The existence of a great civilization in Libya and Tunisia even before the time of Sonchis is more than fascinating. This tangent is compelling circumstantial evidence that the Atlantis myth is more tenable than many scholars are willing to assert. We find evidence of this lost civilization in many ruins throughout Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. One of the most compelling is an artefact known as the “Libyan Palette,” (above image) found at Abydos, Egypt. The tablet contains decorative etchings and hieroglyphic writing that hints at ancient cities (before 3200 BC), a land known as Tjehenu West of Egypt (the Libya of Herodotus).

Also part of the sparse archaeological record of this region are remarkable Stonehenge-like trilithons, step pyramids, and many other evidences of advanced Neolithic habitation. A few points should be made here. First, the transformation of this region since the last ice age (11,700 years ago) has been dramatic. The desertification of what were grasslands and forests and the retreat remote nature of megalithic remains now located in uninhabitable wastelands attest to an unknown civilization. The second point to make here is that before Sir Arthur Evans and others began unearthing Keftiu (Minoan) sites, the idea of this pre-Mycenaen world did not exist either. The same holds for Heinrich Schliemann’s and Frank Calvert’s Troy discoveries. I could make an extensive list here, but the potential I am unveiling in this Atlantis thesis should be clear. My question for archaeologists is, “Shouldn’t we consider the Keftiu as, at least, the descendants of an even older and more advanced civilization?’ Imagine a large civilization not having quite reached Bronze Age developmental stages, being visited by the first ships of Keftiu! Forgetting timelines for the moment, how would oral recollections manifest?

On Strange Coincidences

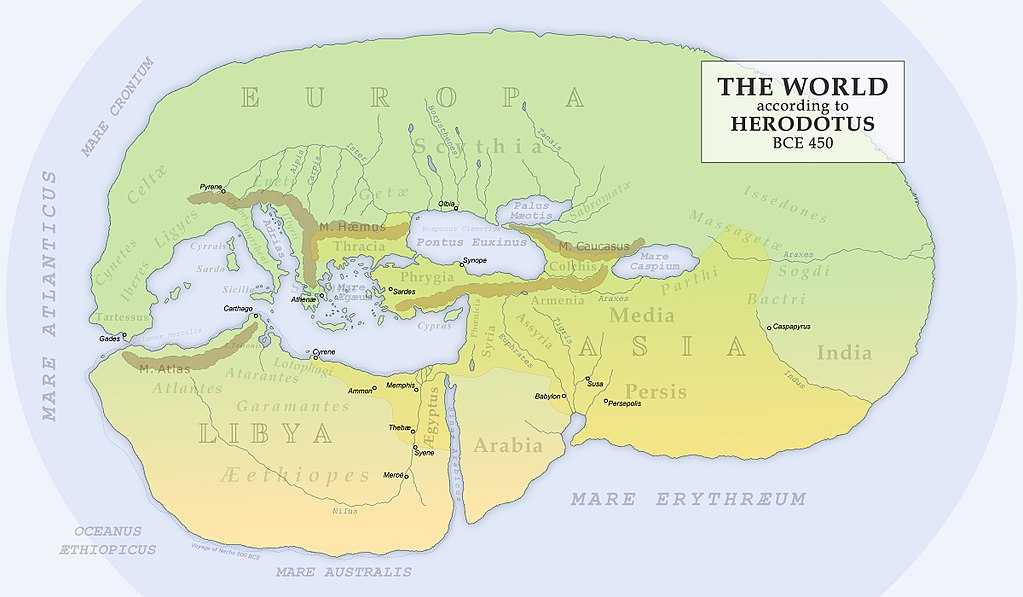

A few scholars during the time of Herodotus would argue that the most knowledgeable and precise historians and archivists of the ancient world were the priests of Sais. Plato insisted that Sonchis of Saïs related the story of Atlantis just as a grandparent might tell a story to a grandchild. It’s important to mention that Sonchis was also the oldest and most learned of these priests. It seems unlikely that Plato or other notable Greek philosophers would somehow bastardize oral history (or story) from such learned priests. Look at Heradotus’ map of the world (above) during the 5th century BC. The graphic reveals a telling piece of our puzzle, too. Look at the relative size and status of Libya to other regions. On maps, all maps, areas and borders are significant.

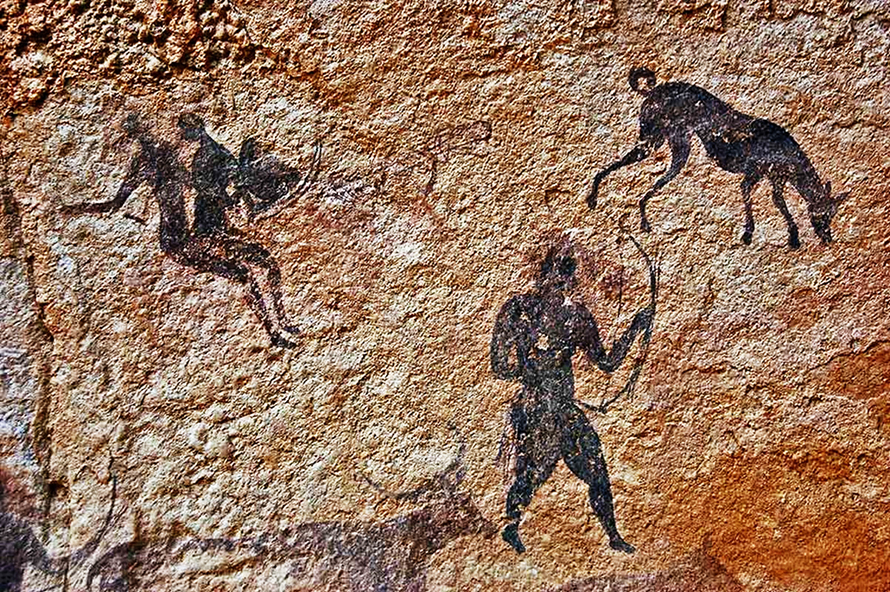

Another interesting “coincidence” concerns me personally as a member of the Cretan Hound Club. Europe’s oldest hunting breed, often called “The Living Legend of Crete,” is a unique primitive canine breed experts are still trying to trace back to its roots. They say, “A picture is worth 1,000 words,” but the image above may be worth 10,000 years.

Due north of Gabes, across what was once a fertile plain and a UNESCO park, Tassili n’Ajjer (Plateau of rivers) has many surrealistic features. The hunting scene you see is from cave paintings depicting an Afrikanis dog very closely resembling the best modern Cretan Hound specimens. These Kritikos Lagonikos, only indigenous to Crete, could be a direct descendant of these Libyan dogs or a carefully bred hybrid from the now-extinct Egyptian Tesem. It’s well known that predynastic Egyptians in the Naqada I period traded Nubia with the people of the West and the South. Tracing the origins of the Atlantis story gets more interesting if we consider possible evidence like these rare and distinctive dogs.